The Impoverished Vaccinator

Newsletter 20. November 1999.

In 1799, the villagers of Finmere were among the first to benefit from Edward Jenner's smallpox vaccine. Jenner, and the vaccinators that followed him, saved millions of people from death and disfigurement. Smallpox remains the only infectious disease totally eradicated by medical science: thanks to Edward Jenner, helped by many enthusiastic vaccinators, including Robert Holt, Rector of Finmere. This Newsletter celebrates the two-hundredth anniversary of Holt's vaccination campaign.

The achievements of Robert Holt are the more remarkable as he was a clergyman untrained in medicine. He recognised the experimental nature of the procedure and documented his results, which were published in the pioneering Medical and Physical Journal in December 1799. Holt's diligent work earned him considerable praise. One of the country's most eminent surgeons, John Abernethy, saluted Holt as:

A gentleman whose character [is] highly estimable for benevolence, learning and love of science.

Holt left few local records of his twelve years in Finmere (1790-1802). If it were not for Derrick Baxby, we may never have discovered Holt's achievements. Derrick, a medical lecturer and virologist at the University of Liverpool, uncovered Robert Holt during his research into the history of smallpox vaccination. He told us of his discoveries and initiated my long hunt for documentation about Holt and his vaccination experiment.

Important documents were found at the Huntington Library in California and in many UK libraries. A few weeks ago, just as I was beginning to write this newsletter, Ian Baker of Southampton was browsing the FHS Internet site. Ian is the great-great-great-great grandson of Robert Holt and has been able to add much to my knowledge of Holt's family.

Now, with particular thanks to the people and organisations noted on the back page, the Holt story can be told. The story tells of how a poor man from Lancashire became friends with aristocrats and cared for the poor of his parish. It tells also of the constant battle against poverty and disease. Robert Holt lost this battle. He died in Finmere, bankrupt at the early age of forty-one.

Robert Holt, Scholar and Rector

Robert Holt was born to a working family in Rochdale, Lancashire, on 15 February 1761. His family moved to Manchester where he attended Manchester Grammar School and his father, also Robert, worked as a bookbinder.

Holt was a bright scholar and won a Somerset Scholarship to Brasenose College, Oxford. This provided him with lodgings and 5 shillings a week. At Brasenose, he studied classical and biblical studies, with some rhetoric and logic, but probably not medicine. He was awarded a Batchelor of Arts in January 1786 and an MA in July 1789.

During his studies, he returned to Lancashire to marry Sarah Fowler, five years his junior. They were wed in St Helens on 16 December 1787 by William Finch, Sarah's brother-in-law.

An intelligent and amiable scholar, Holt attracted the attention of William Cleaver, the President of Brasenose College. Cleaver was also Rector of Finmere and had previously been chaplain at Stowe for George Grenville, Marquis of Buckingham. After receiving his Masters, and no doubt at Cleaver's recommendation, Holt left Brasenose for Stowe to become chaplain and to tutor George's son.

The son was Richard ("Dick") Temple, later to become the first Duke of Buckingham and Chandos. He is best remembered for driving his family to the brink of bankruptcy. Dick was encouraged to follow in Holt's footsteps to Brasenose but he did not enjoy it. On 10 October 1793, he complained to Holt:

I understand this to be the last winter thank God that I shall pass at Oxford, as in case the war [in France] is over next summer, I shall go abroad, a period to which I look forward with great pleasure as I should have no objection to leave Oxford immediately.

Robert and Sarah Holt would have been impressed with the magnificence of Stowe. The steady investment by the Grenville-Temple family had created a grand house set in 250 acres of one of the finest landscape gardens in Europe. The couple also visited London where they resided at the family's luxurious home, Buckingham House, on Pall Mall. All this must have all been very grand for a poor graduate who had relied on scholarships to support his studies. It certainly proved costly and Holt was continually borrowing money from Dick and the Stowe Estate manager Joseph Parrott.

As his debts began to mount, Holt was offered the living at Finmere and, on 23 August 1790, George Grenville instituted him as Rector.

Smallpox

Smallpox spread from person to person without discrimination. It struck the poor and the rich, and killed labourers and aristocrats without mercy. This terrible disease was as large a killer in the eighteenth century as heart disease and cancer are today.

Smallpox was known as the "speckled monster." Sufferers first suspected that they were infected when they developed a fever, headache, stiff muscles, back pain, nausea and exhaustion. These symptoms relented after a few days when a rash appeared on the face. The rash spread inside the eyes and to cover the entire body. Blisters and pustules developed from the rash, which eventually dried into scabs that fell off after a few weeks.

A smallpox victim in Gloucester, 1923

Smallpox killed between 20% and 60% of those infected. The survivors were scarred, "pocked," and many were blinded from corneal infection.

The Variolators

Many physicians and unqualified people sought ways of avoiding the horrors of smallpox. Diplomat's wife, Lady Mary Wortley Montague, caught smallpox in December 1715. It left her without eyelashes and with a deeply pitted skin. Two years later in Turkey, she witnessed inoculation using matter from the pustules of patients with mild cases of smallpox. Most survived to be immune from the disease.

Deeply impressed, Mary introduced this form of inoculation - variolation - to Britain. By the end of the eighteenth century, numerous practitioners offered an inoculation service. An advertisement from Jackson's Oxford Journal is typical:

Wantage Berks, October 3 1768

INOCULATION

Mr Sampson, Surgeon and Apothecary, begs Leave to aquaint the Public, that his first Set of Patients for this Season (who have all had the Small Pox in the most favourable Manner) left his Inoculating House on Monday last in perfect Health; and that his Houses, appropriated for the Purpose of Inoculation, situated near Wantage aforesaid, are now open … for the Reception of Patients … [Mr Sampson's] Terms are as usual.

The Speckled Monster

It is hard to imagine the terror that smallpox provoked in the eighteenth century. Holt described the fear this disfiguring, deadly and devastating disease struck in Finmere:

The small-pox is so much dreaded in this neighbourhood, that all intercourse with the surrounding parishes is interrupted when any one is infected with them.

However, there is no mention of the dreaded disease in Finmere records, and we cannot determine the frequency and severity with which it struck. Fortunately, there are records from nearby villages.

Our informant is Henry Purefoy, gentleman landowner at Shalstone whose diaries and letters from the 1730s and 1740s survive. Smallpox struck the area several times in 1736 and 1737:

Our town of Buckingham is grievously visited with the small pox, the last I heard of it was in threescore houses, so forasmuch as it is universall hope it will soon be over. I thank God our Shalstone folks have escaped it hitherto.

At present wee have the small pox in ye parish wch put us in some fear … Our parish Clerke John Gibbs is lately dead of the Small pox … The smallpox has been very much here and all who have it (but one) died.

Purefoy's letters reveal the care he took to ensure that he and his family were not exposed to smallpox. In 1742, he planned to visit Cheltenham Spa to take the waters, but not if there was a danger of coming into contact with smallpox. Henry wrote to the Postmaster at Cheltenham:

I having occasion to drink your waters at Cheltenham am obliged to write to you, the Postmaster, to let mee know if the small pox be at Cheltenham.

The Purefoys insisted that their servants were free of the dreaded disease:

If [those applying to be servants] haven't had the Small Pox they must set their Hands to a paper to provide for 'emselves in such case because wee have never had it ourselves.

Servants had to sign a contract with Henry's mother, Elizabeth. In 1754, Priscilla Matthews, "a meniall servant," was to receive four pounds a year. Unless, "at any time of her said service [she] be visited with the Distemper of the Small Pox." If that happened, Priscilla was to be dismissed without compensation.

There was greater opportunity for transmission in towns and outbreaks were often severe. A devastating epidemic hit the town of Burford between May and August 1758. The majority of the residents of the town seem to have been afflicted and at least 190 people died, more than one in ten of the population. As far as we know, Finmere never suffered such a deadly outbreak.

The Vaccinators

The Purefoys were averse to risks and did not experiment with variolation. This was potentially hazardous with death rates of between 1 in 3 and 1 in 200 varying with the strain of smallpox and the experience of the variolator. In 1796, Edward Jenner demonstrated a safer method using cowpox vaccine.

The immunity that cowpox offered against smallpox was well known among country folk and Jenner was not the first to recognise that it could be used for inoculation. Jenner's achievement was to translate folklore into scientific experiment. He embarked on systematic observation, carefully documented and published his results, and widely publicised the benefits of cowpox inoculation.

Edward Jenner's experiments began in his home village of Berkeley, Gloucestershire. His inoculation of young James Phipps is one of the most widely told stories in medical history.

Sarah Nelmes, a dairy maid, had become infected with cowpox and, on 14 May 1796, Jenner removed matter from pustules on her hand. He used the matter to inoculate eight-year-old James who developed pustules but quickly recovered. On 1 July, Jenner performed the second stage of the experiment by inoculating James with smallpox. His aim was to see if the cowpox vaccine worked. This was long before medical ethics and the risk Jenner took with the boy's life today seems unacceptable. But without cowpox vaccination, James would probably have been variolated. The experiment could only improve his life chances.

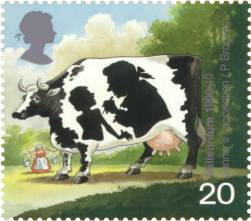

This recent Millennium Stamp by artist Peter Brookes portrays Edward Jenner vaccinating James Phipps with Sarah Nelmes approaching

Jenner's work was controversial, he made mistakes, and there were inevitable detractors. But, following publication of his Inquiry into the Cause and Effects of the Variolæ Vaccinæ in 1798, vaccination rapidly became popular. Five years later, over one hundred thousand people had been vaccinated. Among the first were three hundred residents of Finmere, vaccinated by Robert Holt.

The Finmere Experiment

In the summer of 1799, John Abernethy, founder of St Bartholomew's Medical School, introduced Robert Holt to vaccination:

In conversing with Mr Holt ... on the subject of the cow-pox [vaccine], the favourable report which I made of its effects from my own small experience and observations, induced him, as he takes a kind of parental interest in the sufferings and welfare of his parishioners, to inoculate some of them.

At first, Holt was concerned villagers would be too frightened to take part in his experiment:

The novelty of the vaccination experiment made me apprehensive that my parishioners would not readily submit to an operation which they might consider dangerous in its consequences.

His reservations were misplaced:

My fears were soon removed as I found all impressed by the belief that the cowpox caught in the natural way was a certain preventive of the smallpox.

He began his experiment with Elizabeth Smith who was then twenty-five years old:

I inoculated [her] in both arms to ensure the probability of infection. On the sixth day she complained of headache and pain. She had no pustules, except where I made the incisions … She had no indisposition … and on the thirteenth day the pustules became dry and peeled off.

Within two months, Holt had inoculated 300 people. His supply of vaccine was limited and he increased it by taking matter from the arms of people already vaccinated. The villagers recognised the benefits of vaccination but it was not a pleasant experience:

My cases were all like each other, viz. pain in the axillae the seventh or eighth day, slight head-ach, sometimes attended with feverish shiverings, which inevitably yielded to a dose of salts the day after.

There were exceptions. A painful inflammation of the arm kept baker Thomas Sheen from work for three days. Holt judged that the heat in Sheen's bakery had aggravated the swelling. Seven-year-old Thomas Williams had a small smallpox-like pustule, and William Neal (10 years) and Hannah Beal (6) each had more than one hundred small pustules. But they were no more ill than other vaccinees.

Holt was concerned that William and Hannah might have smallpox. To test this, he drew matter from their pustules and inoculated eight children from them. Fortunately, [the eight] "all had the complaint in its mildest form." Parish records reveal that William Neal lived a long life, dying in 1870, aged 81 years.

Holt supplied fellow clergyman William Finch in St Helens with vaccine. Beginning on 17 November 1799 with David Scarborough, son of a clogger, Finch vaccinated more than 3000 people during the following two years.

An Impoverished Vaccinator

When Robert and Sarah Holt moved to Finmere in 1790, they must have been full of optimism and hope. They retained their links with the northwest while socialising with one of the richest families in England. George Grenville had their Rectory refurbished at a cost of at least £125 pounds. [Correction: this money was used for Glebe House.] Settled in Finmere, Sarah gave birth to five children:

Robert Fowler, 30 June 1791

Sarah Ann, 26 Dec 1792

Mary, 4 Jan 1795

Eliza, 3 July 1796 - died 12 October 1796

William Fowler, 29 October 1797.

For all his good work in the parish, Robert Holt was never free from financial problems. His main income was from tithes paid by the Stowe estate but this proved inadequate. Holt borrowed from his patrons, and then repaid his debts with further borrowings.

In 1793, for example, Dick Temple was short of cash and he demanded repayment of a loan to Holt:

I shall trouble you to send me 40 pounds, as I have been at some expense in regard to my Company [the Buckinghamshire Militia] I shall trouble you to send it as soon as you can...

But Holt had already claimed a £10 advance on his tithe, something he did frequently. He could not pay and, on October 10, he sought a loan from the Stowe Estate manager, Joseph Parrott:

Inclosed is a letter from Lord [Dick] Temple, if you could accommodate him with the money I should be glad, and you shall receive it either from the Bishop or Lord Buckingham [Grenville] with the fortnight.

Parrott paid as requested though he was unhappy with Holt's need to repay the loan through a loan. Parrott was a commanding estate manager and he put pressure on Holt to mend his ways. Acknowledging this, Holt adds to his request "I have learned Wisdom by your last lecture."

But Parrott's lectures were to no avail. Eight years later, Holt was desperately seeking money to repay his debts to the Estate. Eventually, he succeeded and wrote with humility to Parrott:

The inclosed will I trust prove to you that something has been done at last. I have written frequent letters but the inclosed is the first answer I have received.

The loan was from Mr Asheton in Manchester:

I have written by return to close with Mr Asheton immediately, as he is a moneyed man and we shall have it down upon the Mail. I have sent [Thomas] to Northampton to meet the Manchester Mail, so I have lost no time. Another considerable payment this year will make you visit us with a cheerful face.

But Parrott probably did not get his repayments. Robert Holt was dying.

An Early Death

In 1801, Holt sought help from Parrott for his illness:

The Asses you sent are nearly dry and Mr Gray [a Buckingham apothecary] says nothing is so good for me as their milk. You have some [asses] whose young cannot travel, but I beg of you to send them on a cart or some other way, as I am going on well … and I dread a check. I know you will do what you can. I wish otherwise for more seltzer water.

The restorative effects of asses milk were much appreciated during Holt's time and the milk was used to treat a remarkable variety of aliments. Whatever the benefits of this remedy, Robert Holt died on

19 January 1802. He was buried in the nave of St Michael's church on 23 January.

Holt died destitute. Worse, he had misappropriated village charity funds. A churchwarden's note on the apprentice fund records:

Mr Holt enjoy it until Jany 19 1802, by he dying insolvent the money was lost.

Dick Temple's memorial to Holt in St Michael's church record his grief at the loss of his friend:

What kindliness there was in him, according to the poor

What friendship there was in him according to friends

May you readily recognise, therefore, that this was placed in grief and with affection by his companion

Richard Temple

Dick Temple went on, with the help of his son, to bankrupt his family. Widowed and poor, Sarah Holt left Finmere for Lancashire and then moved to Eton. There she ran a lodging house for the boys of Eton School and this allowed her sons to attend the school.

The End of Smallpox

Despite some strong opposition, particularly from variolators, vaccination rapidly became established worldwide. In 1967, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared that smallpox, which still caused more than ten million deaths worldwide each year, was to be eradicated. This was achieved by 1977. Thanks to a movement begun by Edward Jenner and helped by many others, including Robert Holt.

Acknowledgements

I owe a great debt to Derrick Baxby of the University of Liverpool who has helped with many aspects of my research. My thanks also due to Ian Baker, Southampton; Anita Bilbo, Don Imrie, Ian and Sheila Macpherson, Finmere; John Beckett, University of Nottingham; Elizabeth Boardman, Brasenose College; The Centre for Oxfordshire Studies; Penelope Hatfield, Eton College Library; The Huntington Library, San Marino, California; The Jenner Museum, Berkeley, Gloucestershire; Lambeth Palace Library; Lancashire Archives; Manchester City Library and Archives; Oxfordshire Archives; Tina Craig, Royal College of Surgeons Library; The Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine; The World Health Organisation, Geneva.

This is the last newsletter in this series. I hope to continue after publication of the Millennium History of Finmere next year.