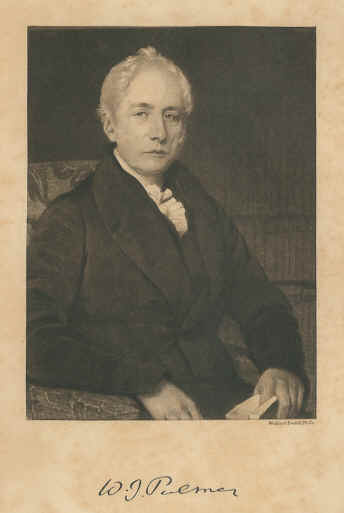

William Jocelyn Palmer

William Jocelyn Palmer had more influence on the development of Finmere than any other rector.

|

|

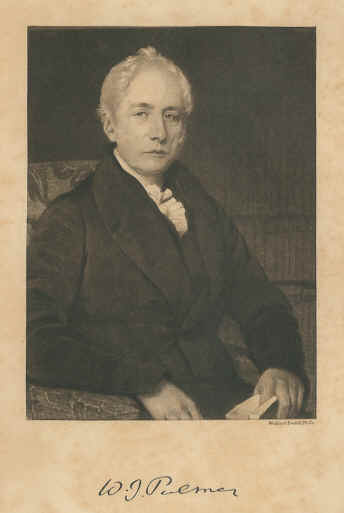

| William Jocelyn Palmer | Dorothea Richardson Palmer |

| Both pictures from Memorials. Part I. Family & Personal. 1766-1865. Roundell Palmer. | |

|

|

Partly based on The Millennium History. Text by Andy Boddington

For much of the first half of the nineteenth century, the parish can be accurately described as Palmer’s Finmere. Although he resided at Mixbury Rectory until 1852, Reverend William Jocelyn Palmer dominated life in Finmere for nearly forty years from 1814. John Burgon described him as a ‘grave good man, who exercised supreme parental and patriarchal authority throughout the parish.’ Palmer took a conscientious interest in the physical and pastoral well-being of his parishioners and brought a period of stability to the church. He made great efforts to improve the lives of the village poor and subsidised the village charities. In return for his benefaction, villagers were expected to abide by Palmer’s strict views of how they should conduct their lives...

Palmer purchased and let eighteen at subsidised rents from 30s to £3 a year, paid half-yearly. He employed a mason and carpenter to keep the cottages in good repair, and provided his tenants with a dinner of beef and plum pudding when they paid their rents. His tenants, however, faced eviction if they did not conform to his ‘conditions of holding,’ including to ‘maintain a fair character for honesty, sobriety, decency, and good neighbourhood in all respects, and at all times, and towards all persons.’ The rules also dictated that tenants’ sons and daughters had to enter work, service or take up apprenticeships once of age. Villagers who obeyed the rules were well cared for by Palmer and his sister, Mary, who lived at Finmere Rectory. Those who crossed him encountered the sterner side of his character…

[In the 1850s] Palmer’s health began to fail under the strain of old age and family problems. His family life had at times been gruelling: his wife Dorothea was seriously ill for several years; a son died at the age of nine; another was lost in a shipwreck homebound from Quebec; a third son, William, caused Palmer considerable anguish as he debated joining the Russian Orthodox Church, finally converting to Catholicism after his father’s death. Under these pressures, Palmer’s judgement began to fail. When the Buckinghamshire Railway cut through the north of the parish, it destroyed meadows in the Rector’s glebe land. Palmer unwisely used the eight hundred pounds paid as compensation to purchase houses and land near the Rectory on the plot of land now occupied by Titch’s Cottage. Six years later, Rector Frederick Walker was given permission to remove the ‘Farm House and Outbuildings divided in Five Cottages.’

As his faculties weakened, Palmer failed to keep the church in repair and his admonitions of parishioners increased. His increasingly cantankerous nature is revealed in his row with Publican Robert Greaves and in his response to the 1851 religious census.

From 1851, he was too ill to discharge his duties. Curate John Burgon took charge of the parish and recorded Palmer’s death:

This saintly man entered into rest on the 28th September, 1853, aged 74 years and 7 months; greatly loved and deeply revered, as well as severely mourned by all that knew him… In compliance with his orders, he was interred in the simplest manner, and sleeps among his children in Mixbury churchyard.

Palmer, William Jocelyn (London).

Com b.j.c. [entered in battery book, paid caution money] and matr. [matriculated] arm. [Army father] [on] 22 Feb. 1796, aged 18.

B.A. 10 Oct. 1799; M.A. 9 July 1802. B.D. 31 Jan. 1811; rem. [removed from College Register] 1848. Died 1853; the father of Earl Selbourne.

More information on Palmer can be found in: